The Museum of Jewish Resistance in Novogrudok opened its doors in 2007. Its establishment is linked to a wealthy man from England, Jack Kagan. He arrived with a specific purpose, which was to restore the memory of those who endured the horrors of the Holocaust and to erect monuments at the sites of mass shootings of Jews in Novogrudok and Novogrudok District. Back in 1943, he was one of those who succeeded in fleeing the local ghetto by night, during what became the largest mass tunnel escape in occupied Europe. He survived as the only member of his family.

Life before the catastrophe

In Novogrudok, Jews lived alongside Belarusians, Poles, and Tatars. Throughout the city’s recorded history, not a single ethnic or religious conflict has been noted. Its inhabitants coexisted in remarkable harmony.

“By 1939, a great many Jews, Belarusians, and Poles identified themselves as ‘locals’ - so unified did they feel,” said Aleksandra Varava, a research associate at the Novogrudok Museum of History and Regional Studies.

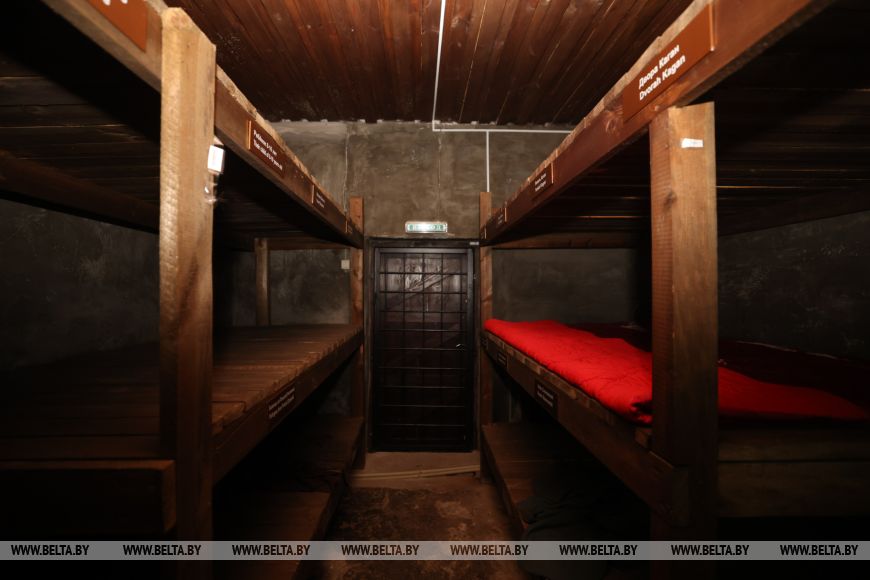

Jews made up a very significant intellectual and artisanal part of the city. The best fur coats and hats could be ordered from the Kushners; the finest horse harnesses could be made by Yankel Kagan. The school attended by Jewish girls was open to all, both Polish and Belarusian students. After graduation, any of them could become a teacher.

Jews made up a very significant intellectual and artisanal part of the city. The best fur coats and hats could be ordered from the Kushners; the finest horse harnesses could be made by Yankel Kagan. The school attended by Jewish girls was open to all, both Polish and Belarusian students. After graduation, any of them could become a teacher.

The Jewish community was instrumental in fostering vibrant commerce and actively advancing the crafts and service industries in the city. In the city center, remnants of the old market stalls can still be seen. “They traded absolutely everything: pork, sausages. In the 1920s, Novogrudok’s Jews were the first to sell colored ice cream. Once a year, very large fairs were held where you could buy absolutely anything, and young people would look for a life partner,” shared Natalya Zhishko, Head of the Department of Ideological Work and Youth Affairs at the Novogrudok District Executive Committee.

On the way to the museum, we had the chance to stroll through the center -Lenin Square. Wherever you look, everything here is steeped in Jewish heritage. The local café building once hosted the first performance of a Jewish theater. All of Novogrudok’s restaurants also belonged to Jews. Visitors noted that the service culture there was exceptionally high, on par with that of Saint Petersburg and Moscow.

On Sovetskaya Street (formerly Yevreiskaya [Jewish] Street) stood a synagogue, damaged during the war years and demolished in the 1960s. Today, only a large parking lot and a handful of cars occupy the spot.

On Sovetskaya Street (formerly Yevreiskaya [Jewish] Street) stood a synagogue, damaged during the war years and demolished in the 1960s. Today, only a large parking lot and a handful of cars occupy the spot.

If in the mid-19th century there were seven synagogues in Novogrudok, by the early 20th century there were already 16. The Jewish community grew very rapidly. The synagogues also provided religious foundations. In 1896, a religious school was established, part of the entire Novogrudok Musar movement, which translates as “Morality”.

“The Jews of Novogrudok held the land on which they lived in very high regard,” Natalya Zhishko said.

By 1941, 6,500 of Novogrudok’s 12,000 residents were Jewish. No one could have imagined the horror that would soon befall the city.

The first victims

The largest mass shooting here occurred on 8 December 1941. Not far from Novogrudok, in the village of Skrydlevo, a huge pit awaited 5,000 Jews. In one memoir by the grandson of Rae Kushner, it was written that he associates this day of execution with the events at Pearl Harbor.

“On that terrible cold December day, stripped naked, they descended into the pit by ladders, lying down as instructed by the police, pressed as tightly together as possible. Then, the 36th Estonian Police Battalion carried out its bloody task: firing upon the defenseless people lying below. History tells us that the clothing of the murdered prisoners, which lay in that enormous pile, was later shamelessly sold by the police at the local market. And the people who bought it, of course, knew nothing of this,” Aleksandra Varava said.

We entered the museum. The first thing that caught the eye was the enormous number of archival photos of local prisoners. It was chilling to look into their eyes - happy, not yet acquainted with sorrow, each preserving their unique history. It was especially difficult to see the photographs of children.

“The driving force behind this museum was not only Jack Kagan. It was all those who lived through the horrors of the Novogrudok ghetto,” says the museum researcher.

“The driving force behind this museum was not only Jack Kagan. It was all those who lived through the horrors of the Novogrudok ghetto,” says the museum researcher.

The second mass shooting took place on 7 August 1942. The day before, 4,000 people had already been liquidated from the ghetto at Peresek. The 500 who remained alive were given work cards and transferred here, to the territory of the voivodeship court, where workshops were already located.

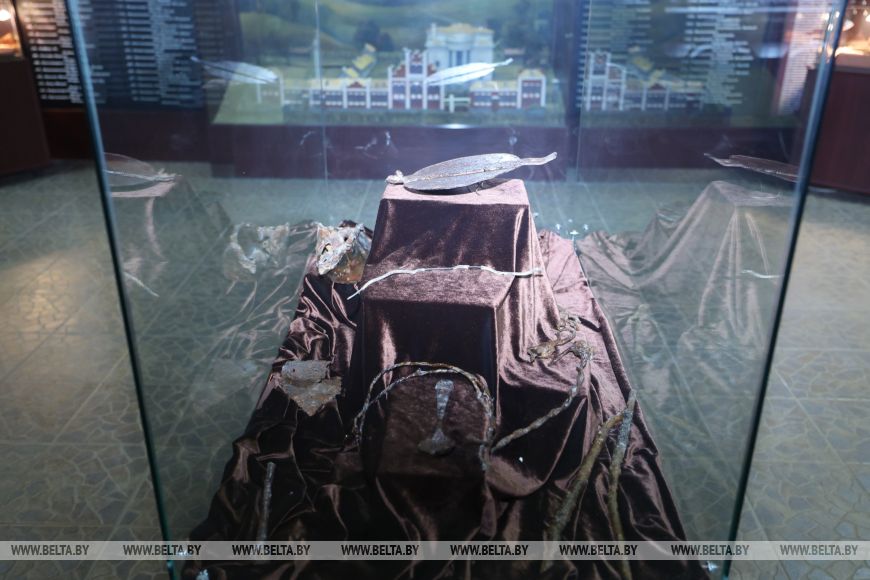

They were met by cold, bare bunk beds, recreated in the museum based on original blueprints. Completely bare planks with a tiny amount of space allocated to each person. Back then, people were even grateful that they were allotted 65 centimeters per person, rather than the 55 centimeters it had been before. Twenty-two people were crammed into one small room. Today, a surname is inscribed in gold letters on each bunk: entire families -the Kushners, the Gorodinskys… And another, mysterious family, identified simply as a family with an infant. In one spot, an untouched mattress lies neatly made, as if time has stood still and the bed is still awaiting its owner’s return.

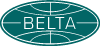

But this was far from the worst of it. Inside the ghetto, people ate leaves and grass, catching anything that flew or ran. These were rodents, and sometimes cats and dogs. A genuine celebration was receiving a small 125-gram piece of bread. And even that was filled with straw. A similar piece is also displayed in the museum - grey, inedible, and hard as a rock.

But this was far from the worst of it. Inside the ghetto, people ate leaves and grass, catching anything that flew or ran. These were rodents, and sometimes cats and dogs. A genuine celebration was receiving a small 125-gram piece of bread. And even that was filled with straw. A similar piece is also displayed in the museum - grey, inedible, and hard as a rock.

“One of the prisoners recalled that he would eagerly await his turn for a bread crust, because that little piece could be chewed on for a long time, almost half the day. And if someone, for whatever reason, didn’t go to work, then those 125 grams were divided among all the family members,” Aleksandra Varava said.

We looked at the model of the ghetto presented in the museum. A solitary searchlight still seems to watch everyone who crosses the threshold of the structure or walks along its perimeter.

Stories of successful escapes from the ghetto are also known. At the age of 12, Idel Kagan attempted to flee in December 1942. But after that, conditions grew harsher. Every escape meant punishment for those who remained imprisoned.

Stories of successful escapes from the ghetto are also known. At the age of 12, Idel Kagan attempted to flee in December 1942. But after that, conditions grew harsher. Every escape meant punishment for those who remained imprisoned.

The thirst for salvation

The last massacre of Jews took place here in 1943. It was a pivotal year in the history of the Great Patriotic War. On 7 May, the Nazis planned to annihilate the last 500 Jews of the Novogrudok ghetto. The method of killing was insidious and cruel.

“Ahead of it, the prisoners were told that some of them, the ‘distinguished ones,’ were to receive a reward: food. The rations were supposedly to be distributed in the building of the voivodeship court. People lined up as usual, knowing and seeing that they had been marked. Then they were locked inside the building, guards posted at the doors, while another 250 were driven beyond the ghetto gates. Just 200 meters away, near a pit, the shooting began,” a museum researcher noted.

The sense of inevitable loss pushed people to think: “How can we escape? Is it possible?” And indeed, there was somewhere to run. Help awaited in the forest: Bielski’s Jewish partisan brigade, who sent word through relatives urging people to flee and seek shelter with them. Tuvia Bielski himself was an ordinary young man with no military training. The place of refuge was nicknamed the “Forest Jerusalem”.

“He offered resistance to those in the most horrific conditions, saying: ‘I cannot promise you will live. But I promise that if you die, it will be fighting.’ In the brigade were not only strong men but even frail old people. He divided it into two parts: the combat group, which blew up bridges and carried out attacks, and the family group, which provided the others with warm clothing and food,” the museum staff member explained.

Toward freedom

Several people worked on the escape plan: leader Daniel Ostashinsky, and Berl Yeselevich, who could be called the engineer and designer of the tunnel through which the prisoners were to escape. The nearly airless space was filled with oxygen through holes in the ceiling so that people would not lose consciousness.

Fifty people dug the tunnel, mostly young men of short stature. Rae Kushner also helped; she had been entrusted with the task of preparing coffee for the commandant and serving it to him.

“What labor it was: to hold yourself together so that neither glance nor gesture would betray how your soul aches for those already killed, those gone, those lost!” the researcher emphasized.

Everything was used, even forks and spoons. We were shown an entrenching tool that was used to load the already dug-up soil. All of it was loaded into a cart and quickly unloaded. First onto the attic, which eventually sagged under such weight. Earth was even poured into a double wall – a mock-up of this is also on display in the museum. And so, step by step, they carved out their freedom for four months.

The prisoners invented their own sign language and spoke only it in the tunnel. They understood each other without words. The work was hard, everything was done at night.

The prisoners invented their own sign language and spoke only it in the tunnel. They understood each other without words. The work was hard, everything was done at night.

The prisoners received a small piece of paper with a surname. The list was compiled in such a way that those who dug were first, then the young ones, and then all the elderly prisoners. On the day of the escape, 26 September, prisoner Zeidel Kushner was so nervous that he simply lost his strength. And then his daughter Raya said that she was giving up her place in the queue, the place for the young ones, and staying with her father.

“They literally dragged him through the tunnel. In heavy rain, wind, and fog, he suggested the girls tie their hands together with ropes. This allowed them to stay together and not get lost. For a whole month, they searched for ways to reach the Bielski detachment. In Zeidel’s memoirs, there is evidence that they first reached a detachment of Belarusian partisans, stayed there for a week, after which the commander gave them food and told them to go to the Jews,” the expert said.

“They literally dragged him through the tunnel. In heavy rain, wind, and fog, he suggested the girls tie their hands together with ropes. This allowed them to stay together and not get lost. For a whole month, they searched for ways to reach the Bielski detachment. In Zeidel’s memoirs, there is evidence that they first reached a detachment of Belarusian partisans, stayed there for a week, after which the commander gave them food and told them to go to the Jews,” the expert said.

However, not everyone managed to escape. More than half were shot by the Germans. We left the museum and found a large memorial wall. Every name of a prisoner of the Novogrudok ghetto is inscribed there. Next to the names are granite bulges resembling bricks. They are placed near the names of those who failed to get out. As if their souls became the foundation for the future life not only of Jews but of the entire population of the Belarusian land. Next to those who broke free thanks to willpower and ingenuity – a void, or a window into the future, letting in the light on a sunny day.

We also saw the preserved remains of those very tunnel fortifications. Our way was lined by a sculpture of the tortured 12-year-old girl Mikhle Sosnovskaya. She tried to escape with her friend. The monument has become a symbol of all those Jewish children who were murdered during World War II.

“What the Jews experienced during the Holocaust is a tragedy not only for the Jewish people but for all of humanity,” Natalya Zhishko believes.

“What the Jews experienced during the Holocaust is a tragedy not only for the Jewish people but for all of humanity,” Natalya Zhishko believes.

Darya VERENICH,

BelTA