The history of our capital fascinates every Belarusian. It has been studied long and closely, yet many mysteries remain unsolved. For several years, large-scale excavations have been underway on the Menka River in the village of Gorodishche, located 10km from Minsk. So, when and where was Minsk actually founded? What was the culture of our ancestors like? What other unknown pages of the city's history remain to be discovered? The research was led by Andrei Voitekhovich, Head of the Department of Medieval and Modern Archaeology at the Institute of History of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus. A BelTA correspondent learns what answers have already been found.

Was the ancient church found?

This year, excavations were carried out on a large ancient settlement. “There is some disappointment. We were looking for traces of a church, which was likely wooden, but it turned out that an estate structure stood on this site in the 17th century. As a result, almost all the layers and structures from the Old Russian period were destroyed. We found materials from that time in almost all layers, in a mixed state, including individual human bones, indicating that there were some burials there, but they were also all destroyed in the 17th century. Part of a brick wall and large pits - the foundations of three tiled stoves - are all that remained of the building itself,” Andrei Voitekhovich said.

Archaeologists found a considerable amount of material there dating from the 16th to the 19th century. “The Old Russian materials are also quite interesting. First and foremost, two book clasps, which testifies that books were located somewhere nearby. At that time, books were exclusively ecclesiastical. An interesting find is a fragment of a Black Sea amphora with an inscribed rune. This indicates that in the 11th century, when the city existed, wine or olive oil was brought here from the Black Sea region. But the owner of these amphorae was a Scandinavian, who marked his vessels in the very language he wrote in, that is, with Scandinavian runes. Among other findings are also a fairly good assemblage of jewelry (women's earrings, several rings), 11th-century ceramic pottery, and other everyday items, locks, and about 5-6 iron keys, several trade seals. In general, these are standard urban materials for the 11th-century period,” he said.

11th-century fire and jewelry finds

Excavations were also carried out on a small ancient settlement. “Traces of a fire, which we identified last year, were recorded across the entire excavation site. Burned items, particularly ceramics, suggest that this fire occurred in the 11th century. Charred arrowheads found there suggest that the fire was caused by a military attack and can be linked to some chronicled events. The small settlement burned down almost completely and was not revived afterward,” Andrei Voitekhovich said.

The most striking find at the small settlement was a stone casting mold, he said. “For the first time in the entire history of researching this complex, we have found such a casting mold. Most notably, it had several depressions carved into it for manufacturing various jewels. Among them was a wide-horned lunula (crescent-shaped pendant). This is an imported, Eastern ornament. It was previously believed that all lunulas found at this complex were imported. But it turns out they were manufactured here, on-site. We will later be able to compare the specimens we have with this mold. It's possible they were cast in exactly this kind of mold. We will also conduct a micro-analysis of the metal particles remaining on this mold to determine what metal the jewelry was cast from,” the archaeologist noted.

Another find is a set of items linked to the inhabitants of the small settlement, including several fibulae (brooches). Among them was a fragment of a Curonian fibula that had melted in the fire. “A very rare find for our territories. The person either perished or lost the fibula during the fire. The person was a Curonian from the territory of Prussia. Perhaps this person was some kind of mercenary who participated in the assault on the city,” he said.

Furthermore, the investigation of the jewelry workshop at the unfortified settlement beyond the Danube stream continued. “We have now extended quite far beyond the workshop itself. We found fragments of jewelry production, including one unfinished small cross,” Andrei Voitekhovich said.

What conclusions have archaeologists reached after years of research?

“The most important thing is that we have proven this site was a full-fledged city, whose heyday was in the 11th century. It was a fairly large city for the 11th century with a classic layout—a citadel, a fortified outer town, and four unfortified settlements. As a result of a large-scale section through the rampart, we studied the entire system of the city's fortifications. These wooden fortifications, which reached a height of 7 meters, were preserved in the form of log-foundations up to 2 meters high. We have fully researched the entire construction of the wall and its subsequent fate. Thanks to dendrochronological analysis, we obtained the exact date when the construction of this wall began. This was the year 997. They began to cut down oaks, transport them, and build this wall. This year can be considered the founding date of the city. This city is undoubtedly the chronicled Mensk on the Menka River,” the scientist emphasized.

Among the found materials from the 11th century are pottery, coins, jewelry, weapons, and tools - all characteristic of the urban culture of that period. The finds attest to the development of numerous crafts, particularly jewelry making. This year, a considerable number of fragments of processed slate, used to make spindle whorls and millstones, were found. Archaeologists suggest a workshop was located nearby.

Fragments of a bone-carving workshop and traces of pottery production have been found. There is also evidence of elite habitation (nobles and princely retinue). “Most importantly, these are two vessel bases with the personal coat of arms of Prince Izyaslav Vladimirovich. This may indicate that the prince himself was at this settlement and that special tableware was made for him. It is clear that the order to build the city on this site was given by Prince Izyaslav, who at that very time occupied the princely throne of Polotsk. Minsk emerged as a city of the Polotsk land, as the center of the southern Mensk volost (district) with a rich rural hinterland. As a result of several attacks (in 1067, 1074), the city was severely ravaged; its urban fortifications were damaged and began to collapse. They were repaired, attempts were made to reinforce them with sand, but this evidently did not help. Цhen Prince Vseslav Bryachislavovich granted the Mensk volost as a princely appanage to his son Gleb, the latter, after surveying the situation, concluded that it would be much simpler, cheaper, and more advantageous to build a new city on the Svisloch River. Which is precisely what he did. And this city on the Menka river gradually, over 20-30 years, completely dwindled into nothing. For some time, it still functioned as a trading transshipment point, and then, somewhere closer to the mid-12th century, life there ceased completely,” he said, summarizing the results of their analysis.

Will the official founding date of Minsk be changed? “We will state our version officially, and then it's up to the city authorities,” the archaeologist said.

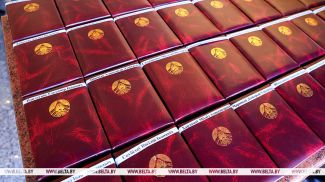

Archaeologists will process the data obtained at the Menka site and then prepare books. “It is planned that all these materials on the history of ancient Mensk will be published in two volumes dedicated to the history of the Old Russian town and the period when a feudal estate existed here. The materials, which are extremely rich, including those from the 16th-19th centuries, are also worth publishing separately. What the book will be called is still unknown,” the head of the expedition stated.

Research will possibly continue next year. “A great deal more can be studied. This archaeological complex is enormous. It is a large town with a fortified settlement and unfortified suburbs. We would like to open several more excavation pits at the large settlement,” Andrei Voitekhovich said. Archaeologists are documenting significant destruction of the Old Russian layers from the 17th-19th centuries, when an estate was functioning on this site. According to the expedition leader, they would like to find Old Russian layers untouched by the activities of later eras.

Valeria GAVRILOVA,

Photos by the Institute of History of the National Academy of Sciences,

BelTA.