... The wind of centuries carries the original beauty of folk art away into oblivion. Only thanks to enthusiastic professionals it is possible to capture time and preserve the works of Belarusian folk genius.

Alina Grishkevich, Honored Figure of Culture of the Republic of Belarus, member of the Belarus Writers Union, BelTA staff writer, the author of the journalistic project “The Destiny of Women, The Destiny of United Belarus”, continues the series about women with a story about Galina Nechayeva.

Galina Nechayeva is from the Chernobyl-hit town of Vetka, Gomel Oblast. She is an art historian, ethnographer, researcher, author and co-author of numerous books on art, Honored Figure of Culture of the Republic of Belarus, director of the Shklyarov Museum of Old Believers and Belarusian Traditions in Vetka (from 1988 to 2018). She continues to work in the museum as an art historian. The staff of the museum sticks to the creative approach to the study of folk art suggested by its founder Fyodor Shklyarov. Galina is among them. In many respects it is thanks to her that the museum has a team of professionals who are in love with what they do, and that Vetka has its own ‘mini-Louvre’ museum today.

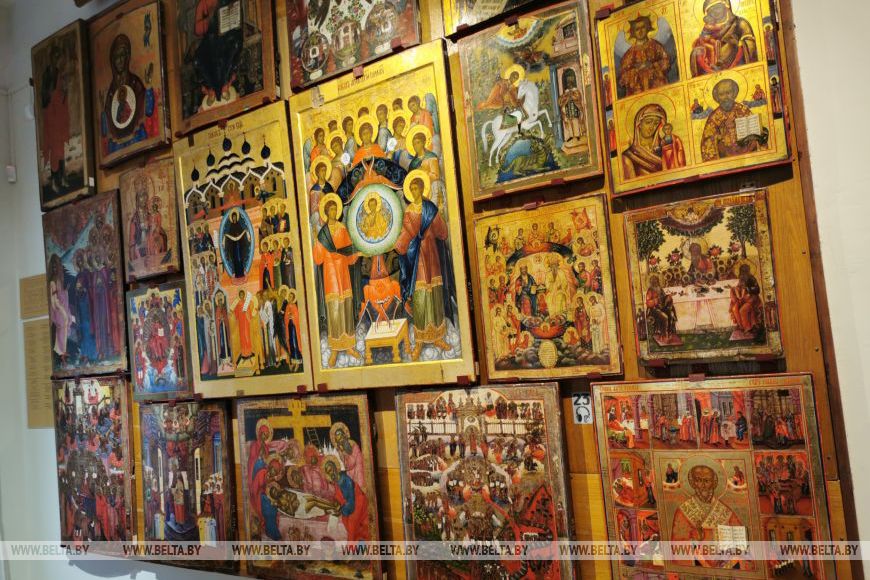

The ancient Old Believers' icons and their heavily decorated cases, Neglubka textile traditions recognized as the national heritage of Belarus… This is a story about the descendant of an Old Believers' family and the town of Vetka that has become a true national treasure trove of arts.

Klondike of southeastern Belarus

The Shklyarov Museum of Old Believers and Belarusian Traditions is located in the time-honored cozy town of Vetka. The museum expositions are worth viewing as they offer a dive into magical world of inexhaustible wealth of Belarusian art.

On my first visit to the museum, I involuntarily drew parallels with what I had seen while traveling abroad. The Louvre, the Musée d'Orsay, the Museum of Modern Art and the Army Museum in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest, the Museum of Modern Art in Slovenia’s Ljubljana, the Charlottenburg Castle in Berlin, the National Museum and many palace complexes in Beijing.

It is impossible to compare them. All these institutions are outstanding for the phenomenal beauty and richness of national and world art traditions.

Of course, every country has its own wonderful places, hubs of national art, which are part of the world art. Millions of tourists flock there to admire the beauty of ancient and modern art. There are no similar museums because each of them reflects something different, special, and national. The older they are, the greater the interest of tourists is.

Vetka also hosts tourists from different regions, countries, including the People's Republic of China. Of course, there are not as many visitors here as in Paris. However, the Vetka museum strikes the imagination, recreating the Belarusian reality of centuries ago.

You would not expect to see in the Chernobyl hinterland the art of such bold beauty and the professional museum expositions or to get a feel of an amazing aura of artifacts from different centuries - as if they are connecting links between generations of the people who once lived and created on our land helping future generations to rise on the civilizational ladder of development.

The Vetka Museum expositions of items collected during numerous expeditions around Belarus for almost half a century are connected by such a living thread.

Thanks to the careful work of the close-knit team of professionals, the museum offers a complex, systemic vision of the centuries-old creative heritage of the Belarusian people, mainly of the southeastern part of our country. From the homemade wooden boats, which our ancient ancestors used to travel along the river, to the goldsmithing of the Old Believers and magnificent Neglubka textile, which has been nominated for the UNESCO world heritage list.

About Galina Nechayeva

She is an amazingly talented person, intimately familiar with the diverse ancient Belarusian heritage. She was born on 22 December 1951 in the town of Vetka. Graduated from the History and Philology Department of Skaryna Gomel State University in 1976. She worked as a teacher and deputy director of the Kazatskie Bolsuny school, and then as a researcher and chief curator of the Shklyarov Museum of Old Believers and Belarusian Traditions. Since 1988 she served as the director of this institution for almost 30 years. Under her leadership the museum became a unique center for the study, systematization and popularization of traditional folk culture.

The museum has systematized the expositions and scientific studies and books prepared based on the results of the research. In particular, the first album “Vetka Museum of Folk Art” (published in 1991) was followed by the “Scientific Records of Vetka Museum” and “Ornaments of the Dnieper River Region”. Unique is the monograph “Voices of Gone Villages”, which in 2008 won the Presidential Spiritual Revival Award. The large books “Living Faith. Vetka” and ‘Vetka's Book Culture’ were published in 2012 and 2014. The latter edition is co-authored by Galina Nechayeva and Svetlana Leontieva. They both have been working at the museum since 1979 and started together with Fyodor Shklyarov. Galina Nechayeva has also authored the books of lyrics and graphics.

Once a young dreamer with romantic aspirations, who knew absolutely nothing about museum work, Galina Nechayeva grew from an employee of the museum to its director. Now she is an art historian and feels great in this role, having given up the place to a new generation. She still remains the heart of the team.

For this woman, the museum, its constant development, continuous expeditions in search of artifacts around villages of the region and documenting and analyzing everything became the work of a lifetime.

Old Believer roots from father's side

However, first things first. How a girl from a traditional Old Believer family came to understand the importance of daily painstaking work for research, search and preservation of folk art?

...On her father's side, her great-great-grandfather, grandmother and grandfather came from Vetka’s Old Believers.

Long ago, in the 1960s, her father (who died in 1996) asked his uncle about their ancestors in a letter.

“Grisha, you ask who your ancestors were. All the Nechayevs are from the river line. Your grandfather Nikita Ivanovich was a captain of a steamship of the Verkhnedneprovsky steamship company. Ivan Nikolayevich, Nikita Ivanovich's father, was an ataman.” She found this letter in the family archive after the death of her father.

There were Zaporozhye Cossacks in the family lineage with all their legends that fascinate the imagination.

Ivan's three grandfathers with Nikitich patronymics

“My grandfather Porfiry Nikitich had three brothers. All three were named Ivan - they were all Ivan Nikitich Nechayevs. In order to tell them apart, they were simply called Senior, Middle and Small, or Black, White and Small. White had two different eyes - one blue, the other brown. This peculiarity was passed through several generations. Ivans were born one after another in 1880-1890,” the woman recalled her ancestral roots. “Their ancestral house stood in Monastyrskaya Street in Vetka.”

By the way, it was here, not far from the museum, that the Pokrovsky Old Believer Monastery was located. From the end of the 17th century to the 18th century it was the largest center of Old Believers.

Mother's ancestral roots come from the Urals

A story of Galina Nechayeva's mother and her acquaintance with her future husband is interesting as well.

The roots of Inessa Aleksandrovna Timofeyeva (1925-1988) are connected with the Ural region - Gus-Khrustalny and Urshal. This is a branch of the family line that leads to the Urals.

Inessa Aleksandrovna, being a 14-year-old girl, went to the geological technical school. Before the war, in 1939, the students, the oldest of whom was 18 years old, were sent on a training expedition to the Trans-Urals. “The young students were enthusiastically studying rocks, looking for the strategic ore deposits,” Galina continued.

The people there mistook her mother for a local, because she was dark-haired and started speaking to her in Bashkir. So she learned only one phrase in this language: “I don't speak Bashkir”.

Galina remembers all mother's stories, which in her youth she really did not pay attention, which she now regrets very much.

And here is a story of how Galina Nechayeva's parents met. They lived far away from each other. Belarus’ Vetka and the Urals region were not connected by flights or the internet. Their meeting became possible due to a confluence of events.

When Galina's mother studied at the vocational school, she became friends with Karl Omelchenko, a native of Vetka. Karl was drafted into the army and died in action. Galina's mother learned about it from his brother Viktor. Some time later Viktor told his cousin about her. They started writing letters to each other, and finally the girl ended up in Vetka.

Galina's father visited his wife's homeland and, when he saw his mother-in-law, he said that he had never seen such a Russian beauty in his life.

Galina’s mother was graceful, fragile, and petite while her father was tall, and both were dark-haired. They were a beautiful couple who built harmonious relationships.

The frontline passed through Vetka for three months

The history of the family, like the history of the entire country, is inextricably linked with the events and tragedy of the Great Patriotic War.

The grandmother recalled: “Our house was moved to another place right after the war; before the war it stood on the corner of Monastyrskaya Street. At the end of 1943 Vetka found itself on the frontline. The fierce battles on the right bank of the Sozh River that went on for three months reduced much of the town to rubble. My father was 15 back then. He lied about his age to be able to join the army. Boys of his age were called up to the army after the war. My father served in reconnaissance, in artillery. The 17-year-old guy returned from the war with a concussion, but he was not dismissed. When the war was over, the young sergeant supervised the work of German POWs who rebuilt Minsk’s avenue that was destroyed by the Nazis, like nearly the entire city.

Galina has a lot of personal stories about the war shared by her elder family members. Her uncle died in a fierce battle during the crossing of the Sozh River. His mother was not able to recover the body until the battles ended. Choking with burning tears, she transported her son's body by boat to the left bank of the river and buried him in the local cemetery...

Tea from a samovar and healing powers of family roots

Galina was born several years after the war, on 22 December 1951. She and her brother, whose name is Aleksandr Grigorievich, were parented very strictly.

She remembered harsh discipline and Old Believer traditions that had a huge impact on her adult life.

Her most striking childhood memories include home feasts, the ancient Old Believer tradition of family tea parties over a samovar, when several generations of the family gathered together. Songs were an important part of such gatherings. As a little girl Galina did not quite understand what these songs were about or what certain tea rituals meant, she just enjoyed the melody and the tea ceremony. She learned later that these songs were about the history of the Old Believers.

By the way, her grandfather’s house, the family nest, is still there. “I live in it in the summer, my grandparents, my parents, lived here,” said Galina Nechayeva.

Here they are, the healing powers of her ancestry. They are invisible, but powerful and unique.

Dream of becoming a writer and artist

As a child Galina was fond of drawing, writing poetry and designing school newspapers. She still remembers her penchant for drawing dream boats.

Nothing indicated that she would choose a career of a museum worker, although she attended a local history club that was run by her mother at the House of Pioneers.

“We were passionate about local history, including archaeology. We even spent 10 days at the site of the largest excavations of an Indo-European burial ground in Vetka District. That's where the love for solving historical mysteries came from, though it manifested itself 30 years later. This love for excavations has remained for my entire life. Museum work is akin to digging. And sometimes I come across some interesting finds in the sand in the river bank after a flood, because our lands are very ancient. By the way, all our archaeological items in the Vetka Museum came from our museum expeditions or were found accidentally. There are a lot of things there that were found and donated to the museum."

University enrollment and work at school

After finishing school in 1969, Galina had to choose a career path.

She recalled: “Since I did not get even basic training in drawing, it was clear that I would not be able to enroll in an art school. My other hobby - writing poetry and essays – looked like a more realistic career path. By the 9th grade, I developed my signature style in writing, I did that with great ease. Therefore, after consulting with my father, I decided to become a writer and enroll in Leningrad University, although the competition there was over the top - 16 people per place. Two attempts to get into this university were unsuccessful. I got an ‘A’ for my essay; only one or two people out of 150 applicants got it. They shook my hand. I went into the hallway and cried, because during my second attempt I was already working at school as a pioneer leader. I put my heart and soul into working with children, I stayed at school until 8-9 pm to arrange and run various events, so I did not have enough time and energy to thoroughly prepare for the history exam (My exam paper question dealt with Suvorov's wars). I knew right away I would not get the pass mark. Yet, the first question, about Rublev's works and the construction of the Moscow Kremlin, got me six points, I spoke enthusiastically about this topic. The teacher lingered by the window, asked me questions, learned that I was from the Belarusian hinterland, probably thought that I should stay in Belarus and gave me a fair C, which canceled out my enrollment aspirations.”

Had he given me a better mark, the Vetka Museum, as it is, would have probably not existed.

After her failed attempts to become a student of Leningrad University, Galina continued working as a pioneer leader. She still wrote a lot, in her notebooks. She entered Gomel University, the Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of History and Philology.

After graduating with honors in 1976, Galina got a job at a village school in Kazatskiye Bolsuny in Vetka District. The work was interesting, but challenging. The 24-year-old teacher had to take over a huge workload because the school was severely understaffed.

Conversation that turned her entire life around

Conversation that changed the trajectory of the young teacher’s life took place in the summer of 1979.

Alina Grishkevich, Honored Figure of Culture of the Republic of Belarus, member of the Belarus Writers Union, BelTA staff writer, the author of the journalistic project “The Destiny of Women, The Destiny of United Belarus”, continues the series about women with a story about Galina Nechayeva.

Galina Nechayeva is from the Chernobyl-hit town of Vetka, Gomel Oblast. She is an art historian, ethnographer, researcher, author and co-author of numerous books on art, Honored Figure of Culture of the Republic of Belarus, director of the Shklyarov Museum of Old Believers and Belarusian Traditions in Vetka (from 1988 to 2018). She continues to work in the museum as an art historian. The staff of the museum sticks to the creative approach to the study of folk art suggested by its founder Fyodor Shklyarov. Galina is among them. In many respects it is thanks to her that the museum has a team of professionals who are in love with what they do, and that Vetka has its own ‘mini-Louvre’ museum today.

The ancient Old Believers' icons and their heavily decorated cases, Neglubka textile traditions recognized as the national heritage of Belarus… This is a story about the descendant of an Old Believers' family and the town of Vetka that has become a true national treasure trove of arts.

Klondike of southeastern Belarus

The Shklyarov Museum of Old Believers and Belarusian Traditions is located in the time-honored cozy town of Vetka. The museum expositions are worth viewing as they offer a dive into magical world of inexhaustible wealth of Belarusian art.

On my first visit to the museum, I involuntarily drew parallels with what I had seen while traveling abroad. The Louvre, the Musée d'Orsay, the Museum of Modern Art and the Army Museum in Paris, the National Gallery in London, the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest, the Museum of Modern Art in Slovenia’s Ljubljana, the Charlottenburg Castle in Berlin, the National Museum and many palace complexes in Beijing.

It is impossible to compare them. All these institutions are outstanding for the phenomenal beauty and richness of national and world art traditions.

Of course, every country has its own wonderful places, hubs of national art, which are part of the world art. Millions of tourists flock there to admire the beauty of ancient and modern art. There are no similar museums because each of them reflects something different, special, and national. The older they are, the greater the interest of tourists is.

Vetka also hosts tourists from different regions, countries, including the People's Republic of China. Of course, there are not as many visitors here as in Paris. However, the Vetka museum strikes the imagination, recreating the Belarusian reality of centuries ago.

You would not expect to see in the Chernobyl hinterland the art of such bold beauty and the professional museum expositions or to get a feel of an amazing aura of artifacts from different centuries - as if they are connecting links between generations of the people who once lived and created on our land helping future generations to rise on the civilizational ladder of development.

The Vetka Museum expositions of items collected during numerous expeditions around Belarus for almost half a century are connected by such a living thread.

Thanks to the careful work of the close-knit team of professionals, the museum offers a complex, systemic vision of the centuries-old creative heritage of the Belarusian people, mainly of the southeastern part of our country. From the homemade wooden boats, which our ancient ancestors used to travel along the river, to the goldsmithing of the Old Believers and magnificent Neglubka textile, which has been nominated for the UNESCO world heritage list.

About Galina Nechayeva

She is an amazingly talented person, intimately familiar with the diverse ancient Belarusian heritage. She was born on 22 December 1951 in the town of Vetka. Graduated from the History and Philology Department of Skaryna Gomel State University in 1976. She worked as a teacher and deputy director of the Kazatskie Bolsuny school, and then as a researcher and chief curator of the Shklyarov Museum of Old Believers and Belarusian Traditions. Since 1988 she served as the director of this institution for almost 30 years. Under her leadership the museum became a unique center for the study, systematization and popularization of traditional folk culture.

The museum has systematized the expositions and scientific studies and books prepared based on the results of the research. In particular, the first album “Vetka Museum of Folk Art” (published in 1991) was followed by the “Scientific Records of Vetka Museum” and “Ornaments of the Dnieper River Region”. Unique is the monograph “Voices of Gone Villages”, which in 2008 won the Presidential Spiritual Revival Award. The large books “Living Faith. Vetka” and ‘Vetka's Book Culture’ were published in 2012 and 2014. The latter edition is co-authored by Galina Nechayeva and Svetlana Leontieva. They both have been working at the museum since 1979 and started together with Fyodor Shklyarov. Galina Nechayeva has also authored the books of lyrics and graphics.

Once a young dreamer with romantic aspirations, who knew absolutely nothing about museum work, Galina Nechayeva grew from an employee of the museum to its director. Now she is an art historian and feels great in this role, having given up the place to a new generation. She still remains the heart of the team.

For this woman, the museum, its constant development, continuous expeditions in search of artifacts around villages of the region and documenting and analyzing everything became the work of a lifetime.

Old Believer roots from father's side

However, first things first. How a girl from a traditional Old Believer family came to understand the importance of daily painstaking work for research, search and preservation of folk art?

...On her father's side, her great-great-grandfather, grandmother and grandfather came from Vetka’s Old Believers.

Long ago, in the 1960s, her father (who died in 1996) asked his uncle about their ancestors in a letter.

“Grisha, you ask who your ancestors were. All the Nechayevs are from the river line. Your grandfather Nikita Ivanovich was a captain of a steamship of the Verkhnedneprovsky steamship company. Ivan Nikolayevich, Nikita Ivanovich's father, was an ataman.” She found this letter in the family archive after the death of her father.

There were Zaporozhye Cossacks in the family lineage with all their legends that fascinate the imagination.

Ivan's three grandfathers with Nikitich patronymics

“My grandfather Porfiry Nikitich had three brothers. All three were named Ivan - they were all Ivan Nikitich Nechayevs. In order to tell them apart, they were simply called Senior, Middle and Small, or Black, White and Small. White had two different eyes - one blue, the other brown. This peculiarity was passed through several generations. Ivans were born one after another in 1880-1890,” the woman recalled her ancestral roots. “Their ancestral house stood in Monastyrskaya Street in Vetka.”

By the way, it was here, not far from the museum, that the Pokrovsky Old Believer Monastery was located. From the end of the 17th century to the 18th century it was the largest center of Old Believers.

Mother's ancestral roots come from the Urals

A story of Galina Nechayeva's mother and her acquaintance with her future husband is interesting as well.

The roots of Inessa Aleksandrovna Timofeyeva (1925-1988) are connected with the Ural region - Gus-Khrustalny and Urshal. This is a branch of the family line that leads to the Urals.

Inessa Aleksandrovna, being a 14-year-old girl, went to the geological technical school. Before the war, in 1939, the students, the oldest of whom was 18 years old, were sent on a training expedition to the Trans-Urals. “The young students were enthusiastically studying rocks, looking for the strategic ore deposits,” Galina continued.

The people there mistook her mother for a local, because she was dark-haired and started speaking to her in Bashkir. So she learned only one phrase in this language: “I don't speak Bashkir”.

Galina remembers all mother's stories, which in her youth she really did not pay attention, which she now regrets very much.

And here is a story of how Galina Nechayeva's parents met. They lived far away from each other. Belarus’ Vetka and the Urals region were not connected by flights or the internet. Their meeting became possible due to a confluence of events.

When Galina's mother studied at the vocational school, she became friends with Karl Omelchenko, a native of Vetka. Karl was drafted into the army and died in action. Galina's mother learned about it from his brother Viktor. Some time later Viktor told his cousin about her. They started writing letters to each other, and finally the girl ended up in Vetka.

Galina's father visited his wife's homeland and, when he saw his mother-in-law, he said that he had never seen such a Russian beauty in his life.

Galina’s mother was graceful, fragile, and petite while her father was tall, and both were dark-haired. They were a beautiful couple who built harmonious relationships.

The frontline passed through Vetka for three months

The history of the family, like the history of the entire country, is inextricably linked with the events and tragedy of the Great Patriotic War.

The grandmother recalled: “Our house was moved to another place right after the war; before the war it stood on the corner of Monastyrskaya Street. At the end of 1943 Vetka found itself on the frontline. The fierce battles on the right bank of the Sozh River that went on for three months reduced much of the town to rubble. My father was 15 back then. He lied about his age to be able to join the army. Boys of his age were called up to the army after the war. My father served in reconnaissance, in artillery. The 17-year-old guy returned from the war with a concussion, but he was not dismissed. When the war was over, the young sergeant supervised the work of German POWs who rebuilt Minsk’s avenue that was destroyed by the Nazis, like nearly the entire city.

Galina has a lot of personal stories about the war shared by her elder family members. Her uncle died in a fierce battle during the crossing of the Sozh River. His mother was not able to recover the body until the battles ended. Choking with burning tears, she transported her son's body by boat to the left bank of the river and buried him in the local cemetery...

Tea from a samovar and healing powers of family roots

Galina was born several years after the war, on 22 December 1951. She and her brother, whose name is Aleksandr Grigorievich, were parented very strictly.

She remembered harsh discipline and Old Believer traditions that had a huge impact on her adult life.

Her most striking childhood memories include home feasts, the ancient Old Believer tradition of family tea parties over a samovar, when several generations of the family gathered together. Songs were an important part of such gatherings. As a little girl Galina did not quite understand what these songs were about or what certain tea rituals meant, she just enjoyed the melody and the tea ceremony. She learned later that these songs were about the history of the Old Believers.

By the way, her grandfather’s house, the family nest, is still there. “I live in it in the summer, my grandparents, my parents, lived here,” said Galina Nechayeva.

Here they are, the healing powers of her ancestry. They are invisible, but powerful and unique.

...Back when she was a child, her grandmother Anastasia Fyodorovna solemnly put a beautiful large, boiling and noisy, five-liter samovar on the table. It could boil enough water for 25 glasses (she remembered this well), and on top of it towered a teapot with Indian or Chinese tea.

“When the elders were finishing another glass of fragrant hot tea, they would say: Nastenka, put another little samovar on for us. The Old Believers loved diminutive and affectionate words,” Galina said. “They would drink tea and indulge in lengthy conversations, exchanging views, sharing secrets. Alcohol was barely needed to have good cordial discussions. The Old Believers have a deep-rooted tradition of tea drinking despite their rejection of novices, although tea was such a novice back in the 17th century. During family gatherings, people sang very beautiful folk songs, soulful romances. I also remember long white hand-woven towels hanging on the shoulders to wipe away the sweat that dripped during such tea parties. My grandmother did not weave. These tablecloths were made by my great-grandmother, I saw her hand-made items when I was a child, and my grandmother showed me the process of making such things.

And again Galina drew parallels: “I worked in the museum for half my life before I fully understood the meaning of the words of the song “Glorious Sea, Sacred Baikal”. This song refers to the displacement of the Vetka residents during the second expulsion of the Old Believers from the Belarusian lands in 1764. Vetka was completely burned down and the Old Believers were uprooted and driven from their homes. According to various estimates, from 15,000 to 40,000 people were resettled, including in the newly acquired territories that had to be developed in the time of Catherine the Great”.

“One of the songs mentions Nerchensk, the Nerchensk regiment. As it turned out, it is also related to the history of the Vetka colony of the Old Believers, who then settled in Transbaikal. The Old Believers kept touch with each other after resettlement despite the huge distance. When tourists from Transbaikal came to our museum, they recalled the stories of their ancestors displaced from Vetka. Their family stories trace back to 1764 and when they come here, they perceive Vetka as their ancestral homeland,” Galina said. She herself has been studying the history of the Old Believers for many years already.

“It is one thing when you study the history of the Old Believers as an impartial researcher. And it is different when you have a personal connection to it. I once made a promise to my late grandfather who was my best friend when I was a child that I would preserve the legacy of our ancestors: our customs, crafts, and art. “It would be a betrayal to let these things fade into obscurity,” Galina said. She dedicated her life to preserving, systematizing and promoting the folk art of her ancestors and her country.

She philosophically remarked: “Otherwise, why live if everything would fall into oblivion?”

She expanded on this topic in her book Vetka Icon that was published in Russian and English in 2002. In this book she shared her impressions, thoughts, her understanding of the Old Believers and the meaning of the icon. It was one of the first books on the art of the Old Believers.

“When the elders were finishing another glass of fragrant hot tea, they would say: Nastenka, put another little samovar on for us. The Old Believers loved diminutive and affectionate words,” Galina said. “They would drink tea and indulge in lengthy conversations, exchanging views, sharing secrets. Alcohol was barely needed to have good cordial discussions. The Old Believers have a deep-rooted tradition of tea drinking despite their rejection of novices, although tea was such a novice back in the 17th century. During family gatherings, people sang very beautiful folk songs, soulful romances. I also remember long white hand-woven towels hanging on the shoulders to wipe away the sweat that dripped during such tea parties. My grandmother did not weave. These tablecloths were made by my great-grandmother, I saw her hand-made items when I was a child, and my grandmother showed me the process of making such things.

And again Galina drew parallels: “I worked in the museum for half my life before I fully understood the meaning of the words of the song “Glorious Sea, Sacred Baikal”. This song refers to the displacement of the Vetka residents during the second expulsion of the Old Believers from the Belarusian lands in 1764. Vetka was completely burned down and the Old Believers were uprooted and driven from their homes. According to various estimates, from 15,000 to 40,000 people were resettled, including in the newly acquired territories that had to be developed in the time of Catherine the Great”.

“One of the songs mentions Nerchensk, the Nerchensk regiment. As it turned out, it is also related to the history of the Vetka colony of the Old Believers, who then settled in Transbaikal. The Old Believers kept touch with each other after resettlement despite the huge distance. When tourists from Transbaikal came to our museum, they recalled the stories of their ancestors displaced from Vetka. Their family stories trace back to 1764 and when they come here, they perceive Vetka as their ancestral homeland,” Galina said. She herself has been studying the history of the Old Believers for many years already.

“It is one thing when you study the history of the Old Believers as an impartial researcher. And it is different when you have a personal connection to it. I once made a promise to my late grandfather who was my best friend when I was a child that I would preserve the legacy of our ancestors: our customs, crafts, and art. “It would be a betrayal to let these things fade into obscurity,” Galina said. She dedicated her life to preserving, systematizing and promoting the folk art of her ancestors and her country.

She philosophically remarked: “Otherwise, why live if everything would fall into oblivion?”

She expanded on this topic in her book Vetka Icon that was published in Russian and English in 2002. In this book she shared her impressions, thoughts, her understanding of the Old Believers and the meaning of the icon. It was one of the first books on the art of the Old Believers.

Dream of becoming a writer and artist

As a child Galina was fond of drawing, writing poetry and designing school newspapers. She still remembers her penchant for drawing dream boats.

Nothing indicated that she would choose a career of a museum worker, although she attended a local history club that was run by her mother at the House of Pioneers.

“We were passionate about local history, including archaeology. We even spent 10 days at the site of the largest excavations of an Indo-European burial ground in Vetka District. That's where the love for solving historical mysteries came from, though it manifested itself 30 years later. This love for excavations has remained for my entire life. Museum work is akin to digging. And sometimes I come across some interesting finds in the sand in the river bank after a flood, because our lands are very ancient. By the way, all our archaeological items in the Vetka Museum came from our museum expeditions or were found accidentally. There are a lot of things there that were found and donated to the museum."

University enrollment and work at school

After finishing school in 1969, Galina had to choose a career path.

She recalled: “Since I did not get even basic training in drawing, it was clear that I would not be able to enroll in an art school. My other hobby - writing poetry and essays – looked like a more realistic career path. By the 9th grade, I developed my signature style in writing, I did that with great ease. Therefore, after consulting with my father, I decided to become a writer and enroll in Leningrad University, although the competition there was over the top - 16 people per place. Two attempts to get into this university were unsuccessful. I got an ‘A’ for my essay; only one or two people out of 150 applicants got it. They shook my hand. I went into the hallway and cried, because during my second attempt I was already working at school as a pioneer leader. I put my heart and soul into working with children, I stayed at school until 8-9 pm to arrange and run various events, so I did not have enough time and energy to thoroughly prepare for the history exam (My exam paper question dealt with Suvorov's wars). I knew right away I would not get the pass mark. Yet, the first question, about Rublev's works and the construction of the Moscow Kremlin, got me six points, I spoke enthusiastically about this topic. The teacher lingered by the window, asked me questions, learned that I was from the Belarusian hinterland, probably thought that I should stay in Belarus and gave me a fair C, which canceled out my enrollment aspirations.”

Had he given me a better mark, the Vetka Museum, as it is, would have probably not existed.

After her failed attempts to become a student of Leningrad University, Galina continued working as a pioneer leader. She still wrote a lot, in her notebooks. She entered Gomel University, the Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of History and Philology.

After graduating with honors in 1976, Galina got a job at a village school in Kazatskiye Bolsuny in Vetka District. The work was interesting, but challenging. The 24-year-old teacher had to take over a huge workload because the school was severely understaffed.

Conversation that turned her entire life around

Conversation that changed the trajectory of the young teacher’s life took place in the summer of 1979.

Next door lived an enthusiastic collector, amateur artist Fyodor Shklyarov, who had just started his work on a district museum. “Come work at my museum,” he said to Galina and her friend Svetlana, who still works as the chief curator at the museum. Today she a candidate of science in art history.

“He invited us and we agreed. The school assignment was already completed. Knowing about our romantic natures and commitment, Fyodor Shklyarov did the right choice by employing us. Thus, we agreed on a salary of 64 rubles giving up on our monthly school salary of 240 rubles, which was impressively high for those times. We were Fyodor Shklyarov's first employees. He worked in a small room in the club, which was allocated for the future museum. He worked alone, but he had already had grandiose plans that finally came come true many years later,” Galina Nechayeva said.

By the way, everything worked well thanks largely to her and her friend Svetlana.

“We thought we would find two books on the Belarusian culture and how to develop a museum, and in a year or two a museum of extraordinary beauty would appear like a fairy-tale castle. The museum has turned out to be really great, but its development took a little longer – an entire life,” Galina Nechayeva smiled recalling her naive girlhood dreams.

Interconnection of times and inner universe

Galina Nechayeva's childhood feelings and memories amazingly connected with her predestined mission, i.e. to devote her life to studying the traditions of Old Believers and Belarusian folk art of the region where she lived - the south-eastern part of Belarus.

Those childhood feelings and fragments of knowledge gradually turned into a multifaceted history of the Old Believers, which Galina Nechayeva described in detail in the books she published together with other museum workers as well as in the museum expositions in Vetka.

“We live in this world, and simultaneously we wind an infinite number of turns around our inner center. This is my cosmic terminology,” Galina Nechayeva said. “As we develop along the spiral, we can mentally find ourselves near the very subject that was important for our ancestors. We are mentally exactly over the point where grandfathers were still sitting at the table, singing those songs. You start to recall your childhood memories of their singing. You start to correlate the fragments of your childhood memories with the history of Old Believers. You put everything together – your feelings, memories, and history. And suddenly you have a single chain of historical events with the words of the songs you heard in the past. The songs, for example, were about the history of the second mass deportations of Old Believers and the formation of the Nerchinsk Regiment which also comprised Vetka residents.

She cited Mikhail Lermontov's poem Cossack Lullaby as an example.

Muddy Terek River splashes

Boulders in the shade;

Evil Chechen creeps ashore while

Sharpening his blade;

But your father is a warrior,

Battle-hardened, too:

Sleep, my son, and don’t you worry,

Rock-a-bye.

This small icon I shall give

To guide you on your way:

Place it right before you every

Time you stop and pray;

Think, when bracing for fierce battle,

Of your mother true …

Sleep, my dear, beloved baby,

Rock-a-bye.

“The lullaby song sung by a Cossack woman over her son's cradle is at first perceived as just a poem told by someone near and dear, whose image was created by Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841). The poet himself was a young brave man, who served in the Caucasus. Many years later, already studying Old Believers, I read that in about 1764 there was another mass deportation of the ancestors. I keep finding these endless connections. Some Old Believers went to the Caucasus then, to the Novorossiysk Territory. You can still find ancient Vetka icons there. Collectors from those areas send them here for consultation (with great respect to the Vetka Museum) to check if they are original Vetka icons and to identify the century they belong to. These icons are found, for example, in the Stavropol Territory, in Essentuki. The re-settlement there took place in the 18th century, and the regiment where Lermontov served was partly formed from Cossacks, whose ancestors were from Vetka.”

“I learned this poem when I was a child. I always thought about the lines:

“He invited us and we agreed. The school assignment was already completed. Knowing about our romantic natures and commitment, Fyodor Shklyarov did the right choice by employing us. Thus, we agreed on a salary of 64 rubles giving up on our monthly school salary of 240 rubles, which was impressively high for those times. We were Fyodor Shklyarov's first employees. He worked in a small room in the club, which was allocated for the future museum. He worked alone, but he had already had grandiose plans that finally came come true many years later,” Galina Nechayeva said.

By the way, everything worked well thanks largely to her and her friend Svetlana.

“We thought we would find two books on the Belarusian culture and how to develop a museum, and in a year or two a museum of extraordinary beauty would appear like a fairy-tale castle. The museum has turned out to be really great, but its development took a little longer – an entire life,” Galina Nechayeva smiled recalling her naive girlhood dreams.

Interconnection of times and inner universe

Galina Nechayeva's childhood feelings and memories amazingly connected with her predestined mission, i.e. to devote her life to studying the traditions of Old Believers and Belarusian folk art of the region where she lived - the south-eastern part of Belarus.

Those childhood feelings and fragments of knowledge gradually turned into a multifaceted history of the Old Believers, which Galina Nechayeva described in detail in the books she published together with other museum workers as well as in the museum expositions in Vetka.

“We live in this world, and simultaneously we wind an infinite number of turns around our inner center. This is my cosmic terminology,” Galina Nechayeva said. “As we develop along the spiral, we can mentally find ourselves near the very subject that was important for our ancestors. We are mentally exactly over the point where grandfathers were still sitting at the table, singing those songs. You start to recall your childhood memories of their singing. You start to correlate the fragments of your childhood memories with the history of Old Believers. You put everything together – your feelings, memories, and history. And suddenly you have a single chain of historical events with the words of the songs you heard in the past. The songs, for example, were about the history of the second mass deportations of Old Believers and the formation of the Nerchinsk Regiment which also comprised Vetka residents.

She cited Mikhail Lermontov's poem Cossack Lullaby as an example.

Muddy Terek River splashes

Boulders in the shade;

Evil Chechen creeps ashore while

Sharpening his blade;

But your father is a warrior,

Battle-hardened, too:

Sleep, my son, and don’t you worry,

Rock-a-bye.

This small icon I shall give

To guide you on your way:

Place it right before you every

Time you stop and pray;

Think, when bracing for fierce battle,

Of your mother true …

Sleep, my dear, beloved baby,

Rock-a-bye.

“The lullaby song sung by a Cossack woman over her son's cradle is at first perceived as just a poem told by someone near and dear, whose image was created by Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841). The poet himself was a young brave man, who served in the Caucasus. Many years later, already studying Old Believers, I read that in about 1764 there was another mass deportation of the ancestors. I keep finding these endless connections. Some Old Believers went to the Caucasus then, to the Novorossiysk Territory. You can still find ancient Vetka icons there. Collectors from those areas send them here for consultation (with great respect to the Vetka Museum) to check if they are original Vetka icons and to identify the century they belong to. These icons are found, for example, in the Stavropol Territory, in Essentuki. The re-settlement there took place in the 18th century, and the regiment where Lermontov served was partly formed from Cossacks, whose ancestors were from Vetka.”

“I learned this poem when I was a child. I always thought about the lines:

“This small icon I shall give

To guide you on your way:

Place it right before you every

Time you stop and pray”... Being a Soviet pioneer, I did not even imagine at that time that it was about such important events, big politics, personal destinies and numerous tragedies of people, including Vetka residents. I just wondered how the poet knew about my grandmother, about that small copper icon that stood at our house near the big crucifix. Every time before Easter my grandmother told me to climb on the table and take down the icon covers and that small icon. I cleaned these copper, bronze things on the corner of the house, where there was well washed sand, not far from the slope leading to the river. I used to make a mush of salted tomatoes and sand and polished the tarnished copper or bronze to get the shiny look back.”

These wonderful strokes of memories from childhood and youth joined new knowledge and life experience of adulthood to blossom with new images and recreate a complete picture of a particular historical period of life. Many of the memories of the everyday life of Old Believer families would later lay the basis of Galina Nechayeva’s books revealing previously unknown periods of the history of Old Believers, icon painting, and Belarusian folk art.

Together with her colleagues she tried her best to deliver her vision of the history of the Belarusian folk art and Old Believers in the Vetka Museum. Today the museum gives a lively idea of the original and unique work of many humble geniuses and talents of the Belarusian land, featuring a wide ranges of exhibits including towels, tablecloths, blacksmithing, carpentry and cooperage, icons of local craftsmen and handwritten books.

Joys of motherhood

With work in the museum and endless expeditions coming first in her life, Galina understood she needed to consider having a family.

“I got married late, to my friend Svetlana's brother. Everything happened unexpectedly. He came to Vetka to take his sister out of our Chernobyl-affected area and decided to stay here forever. He worked in the museum as a restorer and a tour guide,” Galina said.

Galina gave birth to a son Ivan in 1990 and for some time parental duties overshadowed the importance of museum work. Things gradually got back to normal. The father took much of the parenting duties from the very start, reading books to his son and teaching him simple life wisdom. The mother hurled herself once again into work. Galina recalls it as a very happy period of her family life.

However, everything fell apart when her husband got ill and passed away a few years later. Her father died at around the same time. A year later her husband passed away. Her son lost his father at the age of 7. That was a long period of life full of grief and tragedy about the loss of one’s loved ones.

Galina found strength in her son, who was growing up and making her happy, and, of course, in her much-loved work. Her work required full dedication, while her son demanded attention. Svetlana, her friend helped her much: “Her son called us parents”. Svetlana also continued to work in the Vetka museum, which both of them devoted their lives to. Any work after hours in Vetka meant that no one was able to pick up her son from the kindergarten in Gomel, where they had already moved by that time. The woman recalls that difficult period of life with great sadness.

Chernobyl’s pain

Another topic of the conversation was the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, which enveloped the cozy Vetka lands with its black cloud, turning a large part of Belarus into a place unsafe for life and health in 1986.

“It is a tragedy,” Galina said briefly about that time and those events. People had to leave their homes. Then the residents of Vetka, which belonged to the Chernobyl resettlement zone, were allocated thousands of apartments all over the country. Galina Nechayeva was given an apartment in Minsk in 1991. This did not bring any joy however, as she had absolutely no desire to move to another place. Finally, she decided not to leave the museum and not to move to Minsk.

If the local museum workers-enthusiasts had left then, there would probably be no such museum in Vetka today.

The Chernobyl topic seems to be gradually fading away. Less people talk and write about it, as the world is facing completely different issues of human security. However, the Chernobyl period has not disappeared from the lives of individual people. Some of them suffer from diseases, others – from their changed lives.

Museum

A visit to the Shklyarov Museum of Old Believers and Belarusian Traditions in Vetka creates unforgettable memories. From the very first look you understand that the museum’s team of enthusiasts put their heart and soul into it.

The carved gateway immediately provides an air of mystery of what to expect inside. Hopes actually come true. The gate and the carvings were made by three people - Fyodor Shklyarov, Galina Nechayeva and Svetlana Leontyeva.

“The museum is my portrait,” Galina says and immediately corrects herself. “Not only mine, but all of us, starting with Fyodor Shklyarov.”

She tells the story about one more person - architect Leonid Osenny, who left to live in another country long ago but is still well-remembered here. He has laid down a very important principle of designing exhibition space, dividing it into three zones - the viewer's zone, display cases and glass zones between the cases.

To guide you on your way:

Place it right before you every

Time you stop and pray”... Being a Soviet pioneer, I did not even imagine at that time that it was about such important events, big politics, personal destinies and numerous tragedies of people, including Vetka residents. I just wondered how the poet knew about my grandmother, about that small copper icon that stood at our house near the big crucifix. Every time before Easter my grandmother told me to climb on the table and take down the icon covers and that small icon. I cleaned these copper, bronze things on the corner of the house, where there was well washed sand, not far from the slope leading to the river. I used to make a mush of salted tomatoes and sand and polished the tarnished copper or bronze to get the shiny look back.”

These wonderful strokes of memories from childhood and youth joined new knowledge and life experience of adulthood to blossom with new images and recreate a complete picture of a particular historical period of life. Many of the memories of the everyday life of Old Believer families would later lay the basis of Galina Nechayeva’s books revealing previously unknown periods of the history of Old Believers, icon painting, and Belarusian folk art.

Together with her colleagues she tried her best to deliver her vision of the history of the Belarusian folk art and Old Believers in the Vetka Museum. Today the museum gives a lively idea of the original and unique work of many humble geniuses and talents of the Belarusian land, featuring a wide ranges of exhibits including towels, tablecloths, blacksmithing, carpentry and cooperage, icons of local craftsmen and handwritten books.

Joys of motherhood

With work in the museum and endless expeditions coming first in her life, Galina understood she needed to consider having a family.

“I got married late, to my friend Svetlana's brother. Everything happened unexpectedly. He came to Vetka to take his sister out of our Chernobyl-affected area and decided to stay here forever. He worked in the museum as a restorer and a tour guide,” Galina said.

Galina gave birth to a son Ivan in 1990 and for some time parental duties overshadowed the importance of museum work. Things gradually got back to normal. The father took much of the parenting duties from the very start, reading books to his son and teaching him simple life wisdom. The mother hurled herself once again into work. Galina recalls it as a very happy period of her family life.

However, everything fell apart when her husband got ill and passed away a few years later. Her father died at around the same time. A year later her husband passed away. Her son lost his father at the age of 7. That was a long period of life full of grief and tragedy about the loss of one’s loved ones.

Galina found strength in her son, who was growing up and making her happy, and, of course, in her much-loved work. Her work required full dedication, while her son demanded attention. Svetlana, her friend helped her much: “Her son called us parents”. Svetlana also continued to work in the Vetka museum, which both of them devoted their lives to. Any work after hours in Vetka meant that no one was able to pick up her son from the kindergarten in Gomel, where they had already moved by that time. The woman recalls that difficult period of life with great sadness.

Chernobyl’s pain

Another topic of the conversation was the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, which enveloped the cozy Vetka lands with its black cloud, turning a large part of Belarus into a place unsafe for life and health in 1986.

“It is a tragedy,” Galina said briefly about that time and those events. People had to leave their homes. Then the residents of Vetka, which belonged to the Chernobyl resettlement zone, were allocated thousands of apartments all over the country. Galina Nechayeva was given an apartment in Minsk in 1991. This did not bring any joy however, as she had absolutely no desire to move to another place. Finally, she decided not to leave the museum and not to move to Minsk.

If the local museum workers-enthusiasts had left then, there would probably be no such museum in Vetka today.

The Chernobyl topic seems to be gradually fading away. Less people talk and write about it, as the world is facing completely different issues of human security. However, the Chernobyl period has not disappeared from the lives of individual people. Some of them suffer from diseases, others – from their changed lives.

Museum

A visit to the Shklyarov Museum of Old Believers and Belarusian Traditions in Vetka creates unforgettable memories. From the very first look you understand that the museum’s team of enthusiasts put their heart and soul into it.

The carved gateway immediately provides an air of mystery of what to expect inside. Hopes actually come true. The gate and the carvings were made by three people - Fyodor Shklyarov, Galina Nechayeva and Svetlana Leontyeva.

“The museum is my portrait,” Galina says and immediately corrects herself. “Not only mine, but all of us, starting with Fyodor Shklyarov.”

She tells the story about one more person - architect Leonid Osenny, who left to live in another country long ago but is still well-remembered here. He has laid down a very important principle of designing exhibition space, dividing it into three zones - the viewer's zone, display cases and glass zones between the cases.

At first the exposition featured ordinary still lifes of furniture and ethnographic corners of former life. But thanks to the culture of the past coupled with the professionalism of the staff the museum, expositions turn into dramas, sometimes detective stories, filled with symbolism and clues to ancient mysteries. The principle of dialogue and animating the objects, typical for the Tradition, turned the artifacts into characters, heroes, and stories from the past that speak directly to the visitor.

Galina Nechayeva and I entered the museum. She immediately warned me: "Don’t let me talk. Otherwise I wouldn’t stop". Indeed, she can talk about the expositions endlessly and with great passion.

"We were the first in Belarus to implement the concept of a color atmosphere in museum expositions and to apply the semiotics to the culture and traditions of our country," she said.

…When you enter the museum, you can almost feel like you rewind history. From the moment you first encounter the expositions, you want to delve deeper into the essence of life in those days, when our ancestors fished, wove, and carved.

Each display case is three-layered. They show the different stages of development in our ancestors' lives.

Galina guided me through the museum like a river of life that flows smoothly through each new period of civilization. One of the expositions called "We have been here for so long" tells about our ancestor’s life since the Middle Stone Age, the Mesolithic period.

Properly arranged expositions of the museum captivate visitors with their ornaments, jewelry, artifacts, and icons.

Rushniks

I would like to draw your attention to rushnik, a cloth made of linen or cotton with embroidery. At first, there were only five rushniks in the museum. Now it has more than 3,000 patterned fabrics. All types of patterned weaving, ranging from tablecloths and women's shirts to rushniks, have the same ornament structure, which forms the basis of a cultural code and connects generations.

The strong connection between the traditions of generations and the vast layer of folk culture can be seen in the ornaments of Belarusian rushniks. According to experts, the weaving works reflect the creation of the world. By the way, the museum staff have mastered all the stages of weaving themselves – from spinning to loom threading and weaving techniques, which are preserved in different local traditions.

The woven items reflect ancient Belarusian mythology and various stages of human life, such as birth, childhood, marriage, and death. All of these ritual items are made entirely from local materials.

"From the very beginning, our museum explores each artifact as a piece of a specific tradition. We identify, collect, and research these traditions. We try to recreate or record them, restore or find evidence of their various codes. These codes include verbal, pictorial, ritual practices, and cultural actions such as hanging a rushnik or conducting a ritual, for example, a wedding ceremony. We can also decode magical beliefs associated with Perun, the god of thunder in Slavic mythology, and Mother-Raw-Earth, the personified image of the Earth in ancient Slavic mythology.”

A significant number of museum artifacts were collected in local villages and during numerous expeditions. It is very important that the museum staff conduct research based on their own materials that they have discovered.

“We probably have the most extensive collections of regional textiles in the world,” Galina said. “For instance, we have famous Neglubka rushniks, which are part of the intangible cultural heritage of Belarus. They have been recognized by UNESCO. The story behind their creation is truly remarkable.”

The museum prints books using an antique machine, following the blueprints from Skaryna's era. Galina's brother, Aleksandr, crafted it from oak.

Each artifact of the museum is handled with the utmost care as a testament to traditional, local culture. The museum interprets these objects by preserving the history of where they were found and, if possible, who they belonged to.

Goldsmithing

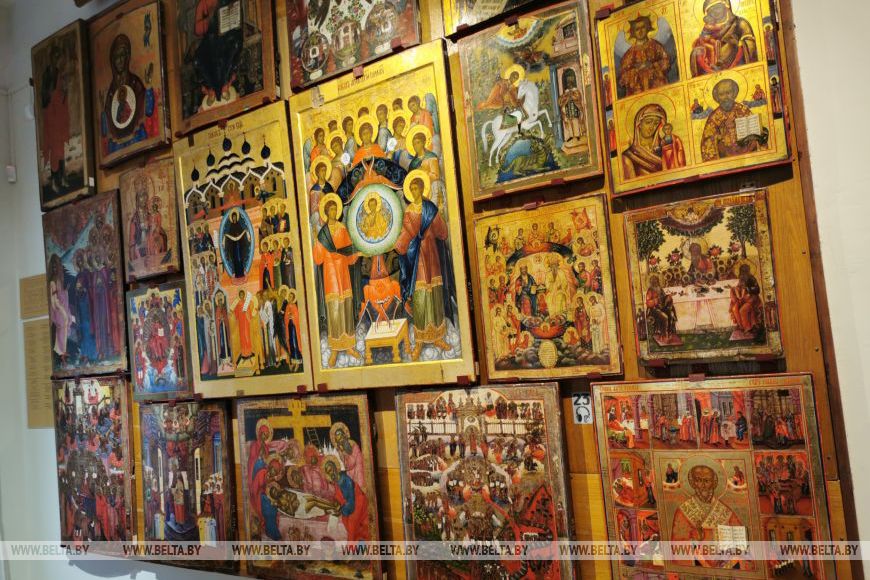

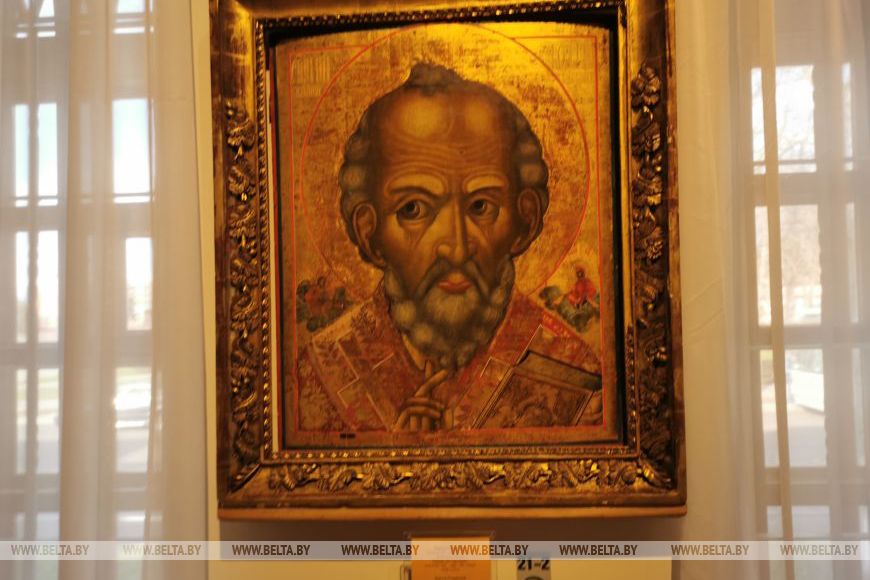

Icons can be admired for hours. Everything about them is magical. The ornamentation of the museum’s icons impresses: gilded frames, river pearls, silver, and chasing. There is a fascinating combination of new historic styles, such as Baroque, Rococo and Empire with Byzantine techniques in Old Believer craftsmanship. This is a huge layer of culture.

On approaching one particular icon Galina says: "This icon is truly unique. It is not just an icon; it is a complex for private prayer. Its concave frame is covered with polished gold. The light source creates an amazing sphere of light. Some of these icons are from centuries ago. They were restored by the Vetka Museum."

The icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, who is believed to prevent troubles, is a symbol of the Vetka Museum.

Finding and acquiring ancient icons is another story. Museum workers are like treasure hunters who know what and where to look for. They are excited when they discover these treasures during their research expeditions.

Galina is a living museum of such expeditions, where the treasures of folk crafts and traditions are found and brought to life. It is impossible to talk about Galina Nechayeva without mentioning the museum.

"The southeastern part of Belarus that we are exploring is a treasure trove of folk art reflecting the amazing culture and history of the Belarusian people. I am sure that there are many artifacts in other regions," she said.

Restoration workshop

The restoration workshop is a sacred place, which gives a new life to ancient icons found during expeditions.

Restorers are dedicated professionals who do a great delicate work. The painstaking labor of these skilled craftsmen is behind many of the items we see on display.

Icons can hide several layers of paint. When masters show the icon before and after restoration, it becomes clear why the process takes so long. The restorers from Vetka adopt best practices and keep in touch with colleagues from Belarus and other countries.

Antique books

The museum takes great care of antique books, which were preserved by the Old Believers in their homes. Now they are given a new lease on life in the museum's exhibitions.

Galina said: “We explore the phenomenon of preserving cultural texts and interacting with personal and regional traditions. This phenomenon can be understood through the example. Once Fyodor Shklyarov brought to the museum an elderly Old Believer. When she saw an old book without a cover, she started stroking it and said: ‘My dear, we have finally met. If my grandfather was alive, he would have wrapped you up in new clothes’.”

Galina Nechayeva frequently argues about the language of creativity: "The museum recreates the diversity of worlds in which our ancestors lived."

Where does she draw her strength from and what guides her through life?

She answered: "Perhaps the family values and traditions nurtured by and passed over from my parents and great-grandparents."

Without realizing it, Galina absorbed the ancient knowledge of several generations of the ancestors. Her understanding of various cultural and folk art processes becomes deeper and deeper. Old Believers are a part of the culture of the Belarusian people, intertwined with the cultures of other countries in a single chain.

A total of 31 people work at the Vetka Museum. There is also a branch of the museum in Gomel. The staff includes researchers and restorers, all with different areas of expertise: history, ethnography, art history, theology, decorative and applied arts. "If you have worked at the Vetka Museum, you are accepted anywhere, because everyone knows you have received excellent training," the staff said.

Annually, about 20,000 people visit the museum, which is open every day. It is surprising that the main exposition includes only 12% of the museum's holdings. Galina explained: "This figure is already big for the museum. We are also engaged in active exhibition activity. Or museum exhibitions are welcomed not only by national Belarusian and regional museums, but also by foreign countries. We are often invited, but rarely take exhibitions abroad, as it is too expensive for a district museum. The Gomel branch is our 'testing ground', where we launch the most daring and innovative projects. For the layman, 'innovative' in relation to traditional art sounds paradoxical. So, if we add the items shown at exhibitions, the figure will increase to almost 25%. Both new ideas and the restored artifacts make their debuts during such exhibitions. In general, exhibitions are an ongoing process of learning the unknown in our own culture."

The Vetka Museum is still a district one, but maybe one day it will become a national museum. However, it can already be called the country’s national treasure trove of art.

Thanks to such unique people as Galina Nechayeva and her colleagues, the museum honors the traditions of the Belarusian people and preserves unique artifacts that reflect the richness and high spiritual culture of our ancestors for future generations.

Galina Nechayeva and I entered the museum. She immediately warned me: "Don’t let me talk. Otherwise I wouldn’t stop". Indeed, she can talk about the expositions endlessly and with great passion.

"We were the first in Belarus to implement the concept of a color atmosphere in museum expositions and to apply the semiotics to the culture and traditions of our country," she said.

…When you enter the museum, you can almost feel like you rewind history. From the moment you first encounter the expositions, you want to delve deeper into the essence of life in those days, when our ancestors fished, wove, and carved.

Each display case is three-layered. They show the different stages of development in our ancestors' lives.

Galina guided me through the museum like a river of life that flows smoothly through each new period of civilization. One of the expositions called "We have been here for so long" tells about our ancestor’s life since the Middle Stone Age, the Mesolithic period.

Properly arranged expositions of the museum captivate visitors with their ornaments, jewelry, artifacts, and icons.

Rushniks

I would like to draw your attention to rushnik, a cloth made of linen or cotton with embroidery. At first, there were only five rushniks in the museum. Now it has more than 3,000 patterned fabrics. All types of patterned weaving, ranging from tablecloths and women's shirts to rushniks, have the same ornament structure, which forms the basis of a cultural code and connects generations.

The strong connection between the traditions of generations and the vast layer of folk culture can be seen in the ornaments of Belarusian rushniks. According to experts, the weaving works reflect the creation of the world. By the way, the museum staff have mastered all the stages of weaving themselves – from spinning to loom threading and weaving techniques, which are preserved in different local traditions.

The woven items reflect ancient Belarusian mythology and various stages of human life, such as birth, childhood, marriage, and death. All of these ritual items are made entirely from local materials.

"From the very beginning, our museum explores each artifact as a piece of a specific tradition. We identify, collect, and research these traditions. We try to recreate or record them, restore or find evidence of their various codes. These codes include verbal, pictorial, ritual practices, and cultural actions such as hanging a rushnik or conducting a ritual, for example, a wedding ceremony. We can also decode magical beliefs associated with Perun, the god of thunder in Slavic mythology, and Mother-Raw-Earth, the personified image of the Earth in ancient Slavic mythology.”

A significant number of museum artifacts were collected in local villages and during numerous expeditions. It is very important that the museum staff conduct research based on their own materials that they have discovered.

“We probably have the most extensive collections of regional textiles in the world,” Galina said. “For instance, we have famous Neglubka rushniks, which are part of the intangible cultural heritage of Belarus. They have been recognized by UNESCO. The story behind their creation is truly remarkable.”

The museum prints books using an antique machine, following the blueprints from Skaryna's era. Galina's brother, Aleksandr, crafted it from oak.

Each artifact of the museum is handled with the utmost care as a testament to traditional, local culture. The museum interprets these objects by preserving the history of where they were found and, if possible, who they belonged to.

Goldsmithing

Icons can be admired for hours. Everything about them is magical. The ornamentation of the museum’s icons impresses: gilded frames, river pearls, silver, and chasing. There is a fascinating combination of new historic styles, such as Baroque, Rococo and Empire with Byzantine techniques in Old Believer craftsmanship. This is a huge layer of culture.

On approaching one particular icon Galina says: "This icon is truly unique. It is not just an icon; it is a complex for private prayer. Its concave frame is covered with polished gold. The light source creates an amazing sphere of light. Some of these icons are from centuries ago. They were restored by the Vetka Museum."

The icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, who is believed to prevent troubles, is a symbol of the Vetka Museum.

Finding and acquiring ancient icons is another story. Museum workers are like treasure hunters who know what and where to look for. They are excited when they discover these treasures during their research expeditions.

Galina is a living museum of such expeditions, where the treasures of folk crafts and traditions are found and brought to life. It is impossible to talk about Galina Nechayeva without mentioning the museum.

"The southeastern part of Belarus that we are exploring is a treasure trove of folk art reflecting the amazing culture and history of the Belarusian people. I am sure that there are many artifacts in other regions," she said.

Restoration workshop

The restoration workshop is a sacred place, which gives a new life to ancient icons found during expeditions.

Restorers are dedicated professionals who do a great delicate work. The painstaking labor of these skilled craftsmen is behind many of the items we see on display.

Icons can hide several layers of paint. When masters show the icon before and after restoration, it becomes clear why the process takes so long. The restorers from Vetka adopt best practices and keep in touch with colleagues from Belarus and other countries.

Antique books

The museum takes great care of antique books, which were preserved by the Old Believers in their homes. Now they are given a new lease on life in the museum's exhibitions.

Galina said: “We explore the phenomenon of preserving cultural texts and interacting with personal and regional traditions. This phenomenon can be understood through the example. Once Fyodor Shklyarov brought to the museum an elderly Old Believer. When she saw an old book without a cover, she started stroking it and said: ‘My dear, we have finally met. If my grandfather was alive, he would have wrapped you up in new clothes’.”

Galina Nechayeva frequently argues about the language of creativity: "The museum recreates the diversity of worlds in which our ancestors lived."

Where does she draw her strength from and what guides her through life?

She answered: "Perhaps the family values and traditions nurtured by and passed over from my parents and great-grandparents."

Without realizing it, Galina absorbed the ancient knowledge of several generations of the ancestors. Her understanding of various cultural and folk art processes becomes deeper and deeper. Old Believers are a part of the culture of the Belarusian people, intertwined with the cultures of other countries in a single chain.

A total of 31 people work at the Vetka Museum. There is also a branch of the museum in Gomel. The staff includes researchers and restorers, all with different areas of expertise: history, ethnography, art history, theology, decorative and applied arts. "If you have worked at the Vetka Museum, you are accepted anywhere, because everyone knows you have received excellent training," the staff said.

Annually, about 20,000 people visit the museum, which is open every day. It is surprising that the main exposition includes only 12% of the museum's holdings. Galina explained: "This figure is already big for the museum. We are also engaged in active exhibition activity. Or museum exhibitions are welcomed not only by national Belarusian and regional museums, but also by foreign countries. We are often invited, but rarely take exhibitions abroad, as it is too expensive for a district museum. The Gomel branch is our 'testing ground', where we launch the most daring and innovative projects. For the layman, 'innovative' in relation to traditional art sounds paradoxical. So, if we add the items shown at exhibitions, the figure will increase to almost 25%. Both new ideas and the restored artifacts make their debuts during such exhibitions. In general, exhibitions are an ongoing process of learning the unknown in our own culture."

The Vetka Museum is still a district one, but maybe one day it will become a national museum. However, it can already be called the country’s national treasure trove of art.

Thanks to such unique people as Galina Nechayeva and her colleagues, the museum honors the traditions of the Belarusian people and preserves unique artifacts that reflect the richness and high spiritual culture of our ancestors for future generations.