A proud posture, a bright multi-layered outfit, but most importantly, the character and sacred meaning of the image. “This Negliubka outfit is for a woman in the prime of her life,” said Tatyana Suglob, the head of the weaving club in Negliubka. She is dressed in vibrant tricolor attire that reflects the soul of the local people.

The local weaving center is happy to welcome visitors. Such a costume, along with the traditional rushnyks (towels) made by local artisans, is considered the calling card of this place, known far beyond our country's borders. Here, history and modernity blend harmoniously. It is precisely here that masters from a long line of craftspeople weave the threads of the past and present, creating a pattern of life for the future.

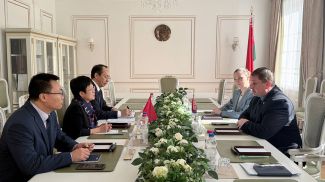

Recently, the Negliubka textile tradition of Vetka District has been added to UNESCO's List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. BelTA’s correspondents visited this remarkable place, met the bearers of this authentic tradition, and uncovered some of the secrets behind the Negliubka style. The fabric of life

The fabric of life

This corner of Vetka District in Gomel Oblast has always been a special place. Local residents have long been renowned for their craftsmanship. The talents of the people of Negliubka were particularly evident in weaving. What began as a practical skill to meet household needs and create domestic comfort grew into a national cultural treasure.

Negliubka - a labor of love

Negliubka textile is unique in Belarusian folk culture. The tradition, which took shape in the 17th century, preserves archaic features and complex symbolism. Towels, garments, and home textiles are known for distinctive weaving and embroidery techniques. It remains alive and continues to evolve to this day. For years, this tradition has been maintained by the Negliubka Rural Weaving Center, with a homely, cozy atmosphere. Modest by modern standards, the space holds treasures that cannot be measured in monetary value.

The creative and organizational process here is led by Lyudmila Kovaleva. A native of Bragin District, she mastered the symbolic language of Negliubka weaving directly from the local masters. She moved here over 40 years ago, established her home and life here.

"Negliubka accepted me in every sense. The people here are kind-hearted, and I learned weaving from scratch. Before, I hadn't even seen a loom like this. Indeed, my hometown also has woven products, but they are completely different. When I arrived here, Negliubka was like a weaving factory: every house had a loom."

Lyudmila cherishes the time when lovers of antiquity and authenticity would visit Negliubka from Russia and beyond. “Our senior weavers dressed up, greeted the guests, told them about our traditions, and sang songs,” she said.

Lyudmila cherishes the time when lovers of antiquity and authenticity would visit Negliubka from Russia and beyond. “Our senior weavers dressed up, greeted the guests, told them about our traditions, and sang songs,” she said.

The local weaving center is happy to welcome visitors. Such a costume, along with the traditional rushnyks (towels) made by local artisans, is considered the calling card of this place, known far beyond our country's borders. Here, history and modernity blend harmoniously. It is precisely here that masters from a long line of craftspeople weave the threads of the past and present, creating a pattern of life for the future.

Recently, the Negliubka textile tradition of Vetka District has been added to UNESCO's List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. BelTA’s correspondents visited this remarkable place, met the bearers of this authentic tradition, and uncovered some of the secrets behind the Negliubka style.

The fabric of life

The fabric of life

This corner of Vetka District in Gomel Oblast has always been a special place. Local residents have long been renowned for their craftsmanship. The talents of the people of Negliubka were particularly evident in weaving. What began as a practical skill to meet household needs and create domestic comfort grew into a national cultural treasure.

The Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO), during its 20th session in New Delhi on 9 December, inscribed the living heritage element “Negliubka Textile Tradition of Vetka District, Gomel Oblast” on UNESCO's List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding.

Negliubka traditional rushnyks (towels) have gained particular fame, distinguished by their complex polychromatic palette (featuring up to 25 shades) and rich ornamental heritage, which includes over 120 patterns, some of which have a thousand-year tradition. The unique traditional costume is also remarkable. This set of traditional clothing bears the codes of life in its design.

Negliubka - a labor of love

Negliubka textile is unique in Belarusian folk culture. The tradition, which took shape in the 17th century, preserves archaic features and complex symbolism. Towels, garments, and home textiles are known for distinctive weaving and embroidery techniques. It remains alive and continues to evolve to this day. For years, this tradition has been maintained by the Negliubka Rural Weaving Center, with a homely, cozy atmosphere. Modest by modern standards, the space holds treasures that cannot be measured in monetary value.

The creative and organizational process here is led by Lyudmila Kovaleva. A native of Bragin District, she mastered the symbolic language of Negliubka weaving directly from the local masters. She moved here over 40 years ago, established her home and life here.

"Negliubka accepted me in every sense. The people here are kind-hearted, and I learned weaving from scratch. Before, I hadn't even seen a loom like this. Indeed, my hometown also has woven products, but they are completely different. When I arrived here, Negliubka was like a weaving factory: every house had a loom."

Once the agricultural cycle ended, women would spend the long winter evenings weaving. In earlier times, they wove primarily to clothe their families; later, they wove items to decorate their homes. “These included bedding, towels, napkins, and tablecloths,” the weaver noted with a smile. Lyudmila Kovaleva added that her own daughter, who now continues the Negliubka weaving traditions in Gomel, has also fallen deeply in love with the craft.

Lyudmila cherishes the time when lovers of antiquity and authenticity would visit Negliubka from Russia and beyond. “Our senior weavers dressed up, greeted the guests, told them about our traditions, and sang songs,” she said.

Lyudmila cherishes the time when lovers of antiquity and authenticity would visit Negliubka from Russia and beyond. “Our senior weavers dressed up, greeted the guests, told them about our traditions, and sang songs,” she said.

The full beauty of Negliubka costumes is demonstrated by local craftswomen and weaving club leaders Tatiana Suglob and Yelena Demchikhina. Each mastered the technique in their childhood. Today, they pass the craft on to their children and grandchildren, as well as to pupils at the local school. Every one of these remarkable Negliubka women is a living treasury of precious knowledge, life stories, and trade secrets.

The uniqueness of the technique

Tatiana Suglob, a hereditary artisan, speaks with affection of her life’s work. “From earliest childhood I remember my mother weaving towels for the house: two colored, two black and white. I remember the silhouette of the loom; I stood nearby and watched. Observation is the first step toward immersion. When I got older, I helped weave bedding during my school years. And in high school, we had a weaving club. We absolutely loved studying there. There were four looms in the classroom, and we hurried to claim one. We started with something simple, like napkins, then moved to more complex pieces like towels,” recalled Tatiana.

She explained the structure of the loom, detailing the role of each part. The weaving center houses several of these large wooden frames, some of which still contain pre-war components.

The loom trains the mind, hands, feet, and imagination, engaging the weaver completely in the work. “There are no limits to the imagination. Sometimes new ideas are born right in the process. A single towel can contain up to twenty shades. When you begin, you never quite know how it will end. All of this guarantees the uniqueness of each piece,” she said.

The process is captivating and painstaking, but it must be done with passion, Tatiana insists. It demands concentration, perseverance, and focus. Mistakes on the canvas aren’t critical, but they cost time, because weaving takes less time than unstitching, as the master puts it. “The uniqueness of the Negliubka technique is that we weave from the back side. We only see the front of the finished work when we turn it over,” explained Tatiana Suglob.

Today, Negliubka towels remain in demand. They are most often ordered for weddings and matchmaking. They are used to tie the hands of the newlyweds, wrap icons for blessing, adorn the matchmakers, or lay on the floor before the couple. Lengths vary, from about 1.5 meters for presenting bread and salt, up to 4.5 meters.

Creating such items can take several days, and sometimes even weeks or months. “If the pattern is simple, we can weave a one-and-a-half-meter towel in two full working days. Then we add the fringe. Overall, the process depends on the complexity of the pattern and the size of the item. In Negliubka, there was a renowned artisan named Valentina Khalyukova: she was petite, yet she wove enormous towels with very intricate patterns. She had a big heart and vivid imagination,” Tatyana Suglob explains.

Inherited craftsmanship

Yelena Demchikhina, the leader of the weaving group, has also been intertwined with Negliubka’s thread since childhood. “As the youngest sister, my mother initially didn’t let me near the loom. She gave me easier tasks, like winding threads on the bobbin. But already in school, during labor lessons and in the young weavers’ group, we started mastering this craft. There were 15 girls for four looms, and we always tried to claim our spot quickly,” she shares. After school, she trained as a women’s dressmaker at a vocational school in Gomel and then returned to weave at the factory in her hometown.

Fate led her to temporarily leave this work, but the loom was always in view at home, so she would return to it in her free time. Now, she has returned to her original craft and teaches it to children. She believes that even in the age of gadgets and technology, children find weaving just as fascinating. “There are talented girls and boys,” she notes.

For her, the weaving process is akin to meditation. “When you are feeling really down, you shouldn’t start working at the machine. But once you get into the process, weaving allows you to escape from everyday problems and issues. Sometimes, I even quietly recite a prayer, just not while laying out the patterns,” Yelena Demchikhina shares.

She has favorite patterns and colors. “I can’t explain why I like them, I just do. There are patterns like ‘eight-point’ and ‘bears’ that come straight from the heart. Each weaver has her own technique, like a signature style or handwriting. Even if we weave the same pattern using the same scheme, the results will still differ. Honestly, I’ve never made two identical towels,” she laughs. Her favorite color palette is the traditional classic of Negliubka: red, white, and black. The experienced weaver believes that this tricolor looks especially festive and ceremonial.

Secrets of true Negliubka attire

Tatyana Suglob and Yelena Demchikhina always gladly try on outfits of the traditional Negliubka style and explain every detail and element of the women’s costume, which is thoughtfully designed down to the last detail.

The most complete collection of attire is gathered at the Vetka Museum of Old Beliefs and Belarusian Traditions named after F.G. Shklyarov. Interestingly, the museum’s junior researcher, Nikolai Asmolovsky, is deeply immersed in the history of Negliubka’s weaving tradition to the extent that he has mastered its unique techniques himself. In his opinion, the entire range of clothing is very interesting, but the core components of the outfits can also be studied through the costumes at the weaving center, where a small fashion show was organized for journalists.

The lowest layer is a long shirt with red woven ornamentation on the sleeves. These elements once revealed a woman’s age and social status. Younger girls had sleeves that were almost entirely white, without patterns; as they grew older, the ornamentation became more prominent. Later in life, more white returned to the sleeves.

“The Negliubka outfit is quite unique and meant for everyday wear. It starts with a richly decorated shirt, which begins at the neckline and extends all the way down to the feet. The red pattern that covers the entire sleeve indicates that the woman is married. As she ages, the amount of red on her sleeves gradually decreases. As a woman gets older, or when her children have all formed their own families and moved out of the parental home, she may wear a simple linen shirt that is traditionally given to her by her daughters-in-law. In return, the mother-in-law gives them a festive headdress – the namitka. This is a traditional Belarusian and East Slavic towel-type headdress, considered a symbol of a married woman. The namitka is a white cloth with woven patterns, tied in a specific way,” museum staff explained as they helped create the image of a Negliubka woman.

The paneva, which was worn over the shirt, was tied in a special way. These were bright woven panels that were fastened at the front and back. One part of the paneva was folded into a scoop shape, forming a pocket just below the back. The geometry of the fastenings did not restrict movement, and it emphasized the dignity and contours of the female silhouette.

“The pocket at the back was for sunflower seeds or apples,” the craftswomen said with cheerful laughter, adding: “That’s what our elders used to joke about.”

“Visually it helps accentuate the features and lines of the silhouette. When a Negliubka woman puts on this festive attire, she is instantly transformed. From a simple housewife she becomes dignified and elegant,” explained Nikolai Asmolovsky.

It is both functional and creates a deliberate play of colors. Against the black fabric, other elements of the outfit stand out in a unique way. This is how the traditional palette is expressed through the costume.

“On top there is another element: the zapina. It can take the form of a ‘golubovik’, an upper apron. It was called ‘golubovik’ because of the blue-sky color of the wool from which it was made. There are also various decorative variations of this element,” Nikolai Asmolovsky said.

Local women also tied a belt. “The traditional Negliubka belt is a spreng. Small tassels were attached to the ends for fullness. Tied in a special way, the belt harmoniously united the upper and lower parts of the outfit. In addition, when twisted into several layers, these elements also served the simple purpose of warming the lower back,” the museum staff stressed.

One of the most distinctive features of the Negliubka costume is the gorliachka, which is similar to a modern beaded choker. “At that time beads were quite expensive, so such necklaces were not wide. They could be purchased from Old Believers. It is important to note that the color palette is also traditional, and the patterns often repeat woven ornaments,” the junior researcher noted.

Another essential element of the Negliubka woman’s attire is the buteli, essentially, necklaces. These decorations, made of shiny, light-catching glass beads, served a dual purpose.

It is not only extraordinarily beautiful but also believed to ward off the evil eye. This adornment, which calls to mind the glimmer of multiple strands of beads, is the first thing to draw one’s attention. “It was believed that the ‘buteli’ (beadwork) acted like a mirror, reflecting away negative thoughts and looks,” the museum emphasizes.

The look was complemented by “pushki” (earrings). They were called “pushki” (literally “fluff”) because of the material they were made from. To create such earrings, the softest goose feathers were tied into little pom-pom balls.

A silk ribbon was tied at the neckline of the shirt. This was an alternative to buttons, which were practically non-existent at the time, with the ribbons helping create additional volume. Negliubka women often wore “khlestovki” – wide satin ribbons with a cross.

However, there were very few traditional costumes for men. “Among them, shirts with embroidery were the most common. Fairly quickly, these shirts were replaced by so-called ‘shakhterki’ or ‘gutsulki,’ which came into fashion in the 20th century. They were especially popular in the mining region of the Donets Basin, where men, including those from Negliubka, often went to work. Gradually, urban style became more and more common. It was the men who brought fashionable trends from the city. Jokingly, they were called ‘valatsugi’ (wanderers),” a researcher explains.

Weaving the future: New generation of Negliubka masters

The workshop is suddenly filled with the sound of children’s voices as fourth-graders, one by one, come rushing into the Negliubka weaving center.

Karina Baimendinova immediately takes a seat at a huge loom, seeming as tiny as Thumbelina beside it.

With instant concentration, she starts on the assignments from the head of the weaving club, who let the young weaver take over. Her little feet in shiny shoes expertly work the pedals as her hands move in tandem.

The girl came from Kazakhstan and is eagerly studying Belarusian crafts. Her older sister used to attend the classes here, and now it is her turn. “I like everything here. I really love yellow, pink, and green,” she shares her color preferences. “Very cheerful colors, this is already the modern Negliubka style,” Tatyana Suglob says with a smile.

Meanwhile, Vlad Yezersky from the fourth grade is eager to try on something from the Negliubka costume again. The schoolboy literally beams at the adults’ compliments. The young man himself is successfully mastering the weaving loom. He was brought to the club by his older sister. He started as soon as his feet could reach the pedals. At work, this live wire turns into a focused and serious guy. “It was tough in the beginning, sometimes the threads were uneven. My dream is to finish weaving our red and green flag. I really enjoyed creating the little fir tree pattern on a towel. I wove some napkins to take home, and everyone liked them,” the novice weaver says.

His classmate Viktoriya Kaplya, as the teachers say, has mastered the craft quite well for her young age. She seems to have a knack for it, figuring out almost everything right away. Her grandmother used to weave very skillfully.

“I love black, white, and red colors – they are classics. I made napkins for my mom, and I wove a huge blanket for my younger sister. She liked it. Her birthday is soon, so I want to make another little gift. I also want to learn how to knit,” the young craftswoman says, who is keen to continue mastering her skills.

Today Vika worked as a little model, trying on a shirt and headdress with colorful ribbons in the Negliubka style. Admiring herself in the mirror, she also received many compliments. “My grandmother probably wore a costume like this. And someone even called me a doll when I was trying on the outfit,” the girl laughed.

“Look at the atmosphere we have here. It’s good that our center is attached to the school: the children practically live here, they pop in even during breaks. No one forces them to weave. Everything here is voluntary. The children learn our traditions while playing, in fact,” noted Lyudmila Kovaleva.

However, the children are drawn to the creativity center as if by a magnet. Whether it is a genetic calling or a fascination with a unique technique is not so important to the instructors. The main thing is that the thread of the craft is not broken.

Krosentsy Festival

Residents from different regions of Belarus and other countries come to Negliubka to learn more about this unique tradition. Thanks to this technique another holiday has emerged in Vetka District.

“The Negliubka-based weaving festival Krosentsy is a relatively new addition to the cultural calendar of the southeastern region. It is held every two years and attracts many connoisseurs of decorative and applied arts. It is a very beautiful festival. We organize a fashion show in Negliubka costumes, in which even the youngest school students participate. Everyone can see the unique Negliubka towels. There are also master classes on making towels or napkins. It is nice that interest in the Negliubka tradition is still alive,” said Vladimir Kovalev, head of the Negliubka Rural Weaving Center branch. The festival will once again bring together enthusiasts of handicrafts next year.

Fate encoded in the fabric

“Curves,” “spiders,” “apple tree,” “fir tree,” “sparrows,” “crosses,” “fists,” “hooks,” “eight-horned,” and other geometric and floral ornaments carry encrypted wishes for good, love, prosperity, and health.

The towels themselves also had a sacred meaning. These woven products accompanied a person from birth to death.

The colors in a woven work of art also have their own meaning. Sometimes Negliubka women would create new words to describe different shades of the color palette. All these cultural codes are studied and explained by modern local lore experts. Perhaps this is a topic for a separate article.

Thus, this tradition, which has become part of the historical and cultural heritage of Belarus, lives on thanks to its unbroken continuity. Unique techniques and the symbolic language of folk art are passed down from generation to generation. Local residents continue to use traditional textiles in their daily lives and promote the spread of traditional Negliubka weaving practices. It is especially important for the craftswomen that this seed and love for their work sprout in their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

For the people of Negliubka weaving is not just a job or a craft, it is life itself, which continues in new generations. Now this tradition is protected as intangible cultural heritage. Thread by thread, the fabric of life is enriched with patterns, meanings, and sacredness.